The entire purpose of this post: I just plain love this monster with glowing eyes. Made by one of my students.

Tuesday, December 9, 2014

Friday, December 5, 2014

Roman Political Graffiti Gets Modernized

I seem to collaborate with Latin teachers a lot, which is funny because I don't know much about Latin. I mean, I know what my last name means, but that's about it.

I know more now, though. For example, I know that one should never Google "Roman Political Graffiti" because the results will be . . . bawdy. Very, very bawdy. Not that I made that mistake. Every Latin teacher who hears about this project IMMEDIATELY says, "DON'T Google Roman Political Graffiti." I think it's what they teach in Latin teacher educator classes on day 1.

The Project:

In honor of last month's elections, Mrs. Smith wanted her students to consider the relationship between current and past political rhetorics.

I know more now, though. For example, I know that one should never Google "Roman Political Graffiti" because the results will be . . . bawdy. Very, very bawdy. Not that I made that mistake. Every Latin teacher who hears about this project IMMEDIATELY says, "DON'T Google Roman Political Graffiti." I think it's what they teach in Latin teacher educator classes on day 1.

The Project:

In honor of last month's elections, Mrs. Smith wanted her students to consider the relationship between current and past political rhetorics.

First, Mrs. Smith set up a Google Classroom for the class. Because the material would be too risqué for students to search for themselves, Mrs. Smith set up 3 Google Drawing templates that featured images of school-appropriate political graffiti and set it up as an assignment in Google Classroom.

In class, Mrs. Smith gave the students a mini-lesson about the role of graffiti in Roman Political life, from painting over someone else's words to challenging the status quo. She then connected that way of communicating publicly to digital ways of communicating publicly. She had them join the classroom (which took about 30 seconds . . . those 8th graders are getting very familiar with Google classroom) and start working.

Students considered ways to Latinize their names, what they stood for as candidates, and ways they could make the visual image evoke Roman stylings.

Because everything was saved in Google classroom, after students handed in their first draft, Mrs. Smith could comment on ways to improve vocabulary and grammar, ask students to resubmit, and accept their new submissions, all online without having to sift through papers.

And THEN . . . that project was such a success that Mrs. Smith replicated it with her 7th Graders (WITHOUT MY HELP!!!), this time focusing on the 7th graders' trip to Washington, DC and the Greek and Roman influences on the architecture of various memorials. Mrs. Smith again uploaded photos as a template; however, this time, some students used their own photos instead. Each image included a quote (often from the memorial's subject), a Latin saying, and a brief reflection on the experience. Beautiful. (And perfect for those digital portfolios that we're launching!)

Thursday, November 13, 2014

Thinglink & Voicethread . . . which to use?

The conundrum: a Spanish teacher wants her students to explore a piece of art and create a digital presentation. She'd like the presentation to include students speaking, links/videos to external sources, and the ability for students to work collaboratively.

Thinglink and Voicethread both allow for all of these, but they each have benefits and drawbacks.

Here's an example of a Voicethread (poor Dave Baroody is always my example):

The benefits I see: Voicethread's commenting process is simple, it's easy for groups to collaborate because Voicethread was built for conversations, students can draw on a picture as they speak to point viewers to details of paintings, and the groups could have more than one slide per presentation, so they could present more than one image. ALSO, because it's made for collaboration, there's also the possibility of sharing a Voicethread with a Spanish class from another school and connecting across schools.

The drawbacks: the comments are linked to a person rather than a part of the image, and so a person viewing the presentation doesn't know what the comments will be about until she's already pressed the comment. That makes the content of the presentation feel more about the conversation than it feels about the content.

The other option is Thinglink:

Benefits of Thinglink: It's pretty. Really pretty. And the comments are a part of the image, so it's very much a presentation tool, too. Students can collaborate by allowing each other to edit their image.

Drawbacks: Making a class as an educator seems like it would be frustrating. All links have to be external, so if a student wants to add a voice recording or a video, she has to know how to use Soundcloud or youtube respectively. The students can figure these things out quickly, but the number of steps means a larger likelihood of error, a larger digital footprint, and more class time devoted to negotiating the technical aspects of the program.

So, which would you use? I'm torn.

Thinglink and Voicethread both allow for all of these, but they each have benefits and drawbacks.

Here's an example of a Voicethread (poor Dave Baroody is always my example):

The benefits I see: Voicethread's commenting process is simple, it's easy for groups to collaborate because Voicethread was built for conversations, students can draw on a picture as they speak to point viewers to details of paintings, and the groups could have more than one slide per presentation, so they could present more than one image. ALSO, because it's made for collaboration, there's also the possibility of sharing a Voicethread with a Spanish class from another school and connecting across schools.

The drawbacks: the comments are linked to a person rather than a part of the image, and so a person viewing the presentation doesn't know what the comments will be about until she's already pressed the comment. That makes the content of the presentation feel more about the conversation than it feels about the content.

The other option is Thinglink:

Benefits of Thinglink: It's pretty. Really pretty. And the comments are a part of the image, so it's very much a presentation tool, too. Students can collaborate by allowing each other to edit their image.

Drawbacks: Making a class as an educator seems like it would be frustrating. All links have to be external, so if a student wants to add a voice recording or a video, she has to know how to use Soundcloud or youtube respectively. The students can figure these things out quickly, but the number of steps means a larger likelihood of error, a larger digital footprint, and more class time devoted to negotiating the technical aspects of the program.

So, which would you use? I'm torn.

Thursday, November 6, 2014

Happy Collaborating

I've been thinking today about when collaborating really, really works for me as a tech coach. Over the past two weeks, I had a wonderful experience of collaborating with Mr. Rich, a Latin teacher. He had this incredibly helpful analysis sheet that he has been using with students for 25 years, but he wanted to modernize it to meet 21st-Century collaborative learning goals.

I did not understand the Latin part of it.

But when Mr. Rich explained the Analysis Sheet to me, it sounded like, if I could find a way to make drop-down menus in a Google Sheet, there was an online method would meet his intentions perfectly. So I Googled that, and I made the least useful drop-down menu in the history of the world:

Here's how you do it: choose data, select validation, select list of items, type in your list and separate with commas, select save. That's it. I thought, OH! I'm done. Except, I did not understand the Latin, and it turns out that those selections don't actually mean anything.

That was okay, though, because then Mr. Rich and I sat and he explained Latin to me, and we plotted out what the sheet would look like, and I taught him a few things about formatting, and then he went home, watched a webcast about sheets, and built the rest of it.

This morning, Mr. Rich presented about the Analysis Sheet and how it's working with students. In attendance were a Latin student, another Latin teacher, the head of informational technology, the head of the upper school, and me.

Mr. Rich talked about piloting the sheet in his Latin class, describing the ways the students were able to work on the sheet at the same time, in real time, collaborate, take on leadership roles and (this was my favorite) participate from home. He also explained how the sheet didn't provide the translation. Rather, it helped students through analysis collaboratively, and then individual students were able to translate the Latin. Also, he referenced the book we're all reading as a teaching community, #EdJourney by Grant Lichtman.

So then my heart was bursting with thoughts about participatory learning, distributed expertise, design, authentic audiences, and other learning theories that make me happy.

Then my negative side thought, "Wait. I didn't do anything. I just figured out how to make a drop-down menu."

I told my negative side to be quiet, and I thought about some of the reasons that collaboration worked. So, here's my analysis of why it was such a great collaboration.

I did not understand the Latin part of it.

But when Mr. Rich explained the Analysis Sheet to me, it sounded like, if I could find a way to make drop-down menus in a Google Sheet, there was an online method would meet his intentions perfectly. So I Googled that, and I made the least useful drop-down menu in the history of the world:

Here's how you do it: choose data, select validation, select list of items, type in your list and separate with commas, select save. That's it. I thought, OH! I'm done. Except, I did not understand the Latin, and it turns out that those selections don't actually mean anything.

That was okay, though, because then Mr. Rich and I sat and he explained Latin to me, and we plotted out what the sheet would look like, and I taught him a few things about formatting, and then he went home, watched a webcast about sheets, and built the rest of it.

This morning, Mr. Rich presented about the Analysis Sheet and how it's working with students. In attendance were a Latin student, another Latin teacher, the head of informational technology, the head of the upper school, and me.

Mr. Rich talked about piloting the sheet in his Latin class, describing the ways the students were able to work on the sheet at the same time, in real time, collaborate, take on leadership roles and (this was my favorite) participate from home. He also explained how the sheet didn't provide the translation. Rather, it helped students through analysis collaboratively, and then individual students were able to translate the Latin. Also, he referenced the book we're all reading as a teaching community, #EdJourney by Grant Lichtman.

So then my heart was bursting with thoughts about participatory learning, distributed expertise, design, authentic audiences, and other learning theories that make me happy.

Then my negative side thought, "Wait. I didn't do anything. I just figured out how to make a drop-down menu."

I told my negative side to be quiet, and I thought about some of the reasons that collaboration worked. So, here's my analysis of why it was such a great collaboration.

- It was a specific change. The goal was completely manageable because Mr. Rich wasn't trying to change everything. He was just trying to change one thing. How scary is it when you think you need to change everything about your classes all at once?

- It aligned with Mr. Rich's curricular goals. The Latin Analysis Sheet isn't tech integration for the sake of tech integration. The first goal of the sheet is to help students to be better at Latin. The facts that it's collaborative, able to be worked on from anywhere, and available in real time are great, but the Latin is still the point. (I feel like this aligns with the 'redefinition' aspect of tech integration in the SAMR model)

- Mr. Rich wanted to make the change. I don't think that it would have been enjoyable in any way if Mr. Rich had felt forced to change. Because we were both invested in a similar way, our work together was fun.

- I didn't worry about being the Latin expert and Mr. Rich didn't worry about being the tech expert. We used each other's expertise to make a product better than either of us could have achieved individually.

- I spent more time listening and asking questions than I did talking. This, I think is actually the biggest key to collaboration. I'm a bit of a butterfly about tech, flitting from idea to idea. I could suggest a million toys to any teacher with whom I collaborate. But if I had, Mr. Rich would have been overwhelmed and annoyed. I feel like, with this collaboration, because I listened to Mr. Rich, he was able to own the project.

Thursday, October 30, 2014

Coding is not just for Hipsters

A student sent me this screenshot of her coding work from tech class yesterday. I adore the sarcasm of 8th graders. In referencing sarcasm, I might sound sarcastic, but I wasn't being sarcastic. Seriously.

The site we've been using in 8th grade tech is www.codecademy.com. The 8th graders have done block-coding with Alice already, and they were excited to use what they've been calling 'real' code. They were excited, that is, until they realized what one misplaced quotation mark can do to their work.

That time I actually was being sarcastic. The students were interested throughout, although concepts of organization of code came more easily to some than they did to others. Being able to track the students as they coded let me know who needed me to jump in and explain concepts and who would probably be able to create an entire Hipster Lyfe website in 48 minutes.

(please note: the cat links to a local coffee shop that sells free-trade, organic coffee)

Wednesday, October 15, 2014

How do you say, "Creando videos"?

In Señora Bejar-Massey's 8th grade Spanish class, she asks students to record themselves speaking Spanish. Over the course of the year, students collect their videos and are able to reflect on their growth as Spanish speakers. . . awesome.

This year, Señora decided to add a few levels to the technology - students will now upload their videos to a Google Apps for Ed YouTube account (where they can make the video private and share only with Señora). They, they'll hand their assignments in via Google Classroom, and Señora will use Videonot.es to comment directly on the videos.

Because there are so many steps to this process, I'm going to be going to Señora's classes tomorrow to get the students up and running. I made this instruction sheet and posted it to the Moodle, and I thought it might be useful for others, too. I'll update later about any pitfalls I encounter.

Wednesday, October 8, 2014

Padlet & Google Docs as a Way to Go Public with Writing

I didn't mean to write two posts about ways to use Padlet in a row, but with the first 6th grade writing celebration of the year, Mrs. Dougherty wanted to find a way for students to share their writing with each other, and padlet.com it was.

Mrs. Dougherty's runs her English classes in Writing Workshop style, and there's a lot of research on the impact of audience on students' writing. So, launching an online space for students to share, comment, inspire, and generally cheer each other on made a lot of sense.

Here's how we set it up so that the wall is both public and private:

From Mrs. Dougherty's end, she created a wall on padlet.com. For settings, she selected:

Mrs. Dougherty's runs her English classes in Writing Workshop style, and there's a lot of research on the impact of audience on students' writing. So, launching an online space for students to share, comment, inspire, and generally cheer each other on made a lot of sense.

Here's how we set it up so that the wall is both public and private:

From Mrs. Dougherty's end, she created a wall on padlet.com. For settings, she selected:

- Password Protected (so the audience is limited).

- People with the password can write comments (which means that students can post, but can't accidentally delete others' posts)

She also selected the Grid layout so that students didn't accidentally cover up other students' work.

Here's how she asked students to post on the wall:

- Make a copy of your document (that way, you'll have a 'clean' version that no one has commented on).

- Set the sharing parameters so 'anyone with the link can comment' (that way, people can comment, but no one accidentally changes your writing).

- Share the link on the padlet wall, putting your name in the top of your comment box.

What it means is that all of the grade's writing can be collected in one place, but each individual keeps control over his/her writing. They look like this after inserting the link:

As with the cat photos that I mentioned in another post, this is an internetty activity that requires talking to students about community and community values during launch (i.e. what kind of comments do you want on your writing? What kind of comments are appropriate in this forum? What kind are inappropriate?).

Thursday, October 2, 2014

Using Padlet to Frame Discussions

In 8th grade Topics in Media and Technology this rotation, I wanted to show a video called I forgot my iPhone (which, by the way, is great). I wanted to encourage students to think critically about the messages in the video. First, I projected the video and asked for verbal responses. Then, I projected a split screen, and students made notes via Padlet about what specific activities the video said were good based on actions and images they saw:

After watching the video, students read George Couros's critique of the video. They discussed the blog post in small groups, and then posted their group's position statement about cell phones based on his blog post. Using the padlet, we then had a class discussion about cell phones use.

Some of the functions of padlet that are useful: you can create a free account, students do not have to create accounts to post, the owner of the padlet page can set permissions so students don't accidentally delete each other's posts, the owner can set a password so that the padlet isn't public, and the wall updates in real time, so you can see who's posting when. Very useful for directing a class discussion and maintaining a record of students' thoughts.

A word of warning: my first class figured out how to put cat photos in a wall. They did it after an amazing discussion, but if you don't like chaos, you'll want to set ground rules for posting.

Monday, September 29, 2014

Memes for Good, not Evil

The lesson for this 8th grade Topics in Media and Technology class was modified from Dave Baroody's Medieval Memes lesson, and the KQED How to Make a Meme video.

I started class by showing students a meme, and I asked them to tell me how memes work. After they had done that, I explained to them that the walls in my room were bare, and I wanted to make my room the most welcoming room ever. But, I told them, I didn't just mean, "Welcome to tech class." I meant, "You are welcome in this room, and it is a safe space."

They didn't quite get it at first (the first class gave me a lot of memes that had a message of, "Welcome to tech class. Tech class is fun." After the first group of students, I had each class generate a list of identity markers for which people are sometimes excluded, mocked, or ostracized. The lists tended to include socio-economic status, race, ethnicity, religion, gender, sexuality, interests. After making the lists, I explained to the students that I wanted the message of welcome to say, regardless of identity marker, you are safe here.

Then, we talked about text/subtext, the relationship of the words to the picture, the concept of setup on the top line and payoff on the bottom line, and most importantly:

We watched the KQED video as a class, and then students worked in groups of 1, 2, or 3 to make memes.Remember that memes are meant to be funny . . . Annnnnnd these memes also need to be welcoming and kind . . . Annnnnnnd that's the challenge.

I had students save their memes as jpgs to a shared Google folder as they completed them, and I projected the folder on the board, so they could see other people's memes as they were created. In each class, the memes started off pretty not-so-great, and then got better and better as students worked on them and saw each others' creations. It was an active learning process for students to be thinking about how welcoming or not welcoming a message might be and how the person in the image was being positioned.

At the end of class, we took a few minutes to debrief as we looked at each others' memes. Almost every student commented on the fact that it was really hard to be funny and kind at the same time. We talked about how this was hard work, and about how we often don't consider how people are being positioned when we make and share things online.

Annnd phew. Because that's why were were doing the lesson.

One last note: I put this caveat (taken from David Baroody) on the moodle site and shared it verbally as well:

Why would I give you an assignment where I knew you might run into material that may be deemed inappropriate? It is NOT because I am trying to corrupt you!

As a citizen of the digital world, you need to realize that the internet is an ENORMOUS place, and that inappropriate content, information, and individuals are out there.

More important than just realizing it's there, though, you need to understand how to protect yourself and others from images, links, and other content in which you (or others) do not wish you to engage. As an educator who employs an increasingly large amount of digital technology, I would rather have an open discussion about this with you, your peers, and your parents than ignore the issue.

If you are interested in some of the theory behind digital citizenship, please look over the Nine Elements of Digital Citizenship here.

Tuesday, September 23, 2014

How Do We Really Get to Know Our Students? iMovie!

Because all of Ms. Bo's students are new to the middle school, Ms. Bo knows that helping them to feel known is key to a successful start. So, the first unit of Ms. Bo's history class investigates primary sources. The class talks about the ways their identities impact their understanding of history, and they talk about the fact that they are the best sources for information about themselves.

In the past, Ms. Bo has had each student create a collage that demonstrates investigation into the source that is their self. Then, the students write an 8-10 sentence paragraph about the collage and the interpretation of their self.

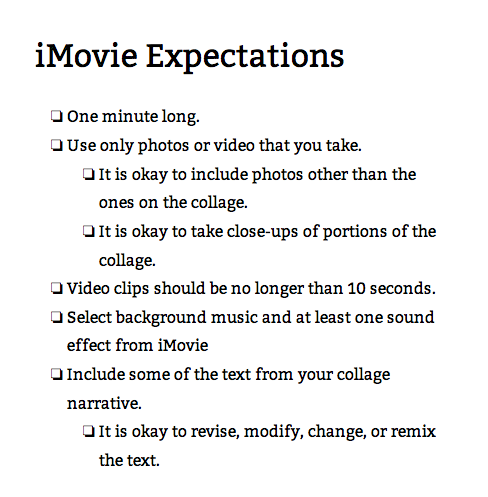

This year, Ms. Bo decided to incorporate iMovie as a digital collage, so I had the chance to collaborate with her. To keep the project manageable, we came up with this list of criteria that we shared with the students as a Google Doc:

We asked for one minute so it was easy to share, and we had students stick to pictures they took and stock music and sound because we didn't want to compound what they needed to know about citation for the project. Since each student had a computer with iMovie already, we didn't have to worry about access, but Ms. Bo made sure to schedule plenty of in-class time to work so she could identify potential hiccups students had with using the program.

When Ms. Bo introduced the project, she first asked the students what you need to make a movie. The students shouted out ideas like a script, actors, scenery, music. Ms. Bo pointed out that they had a script: the paragraph they had already completed, and they had an actor: themselves, and they had scenery: the music. Then, I did a mini-lesson on how to use iMovie, and we let them work. We posted the instructions to Moodle as well:

The students had a lot of questions about whose picture they could use - they REALLY wanted to use photos from the internet. They also REALLY wanted to use copyrighted music. We stuck with no.

When the students went home to work on the projects, they sent Ms. Bo a lot of alarmed emails about the project, which surprised us because in class, they had seemed so on top of it. The next day, in class, it turned out that the students completely had the hang of using iMovie. We weren't entirely sure why they panicked . . . maybe because it was new to them and they were still adjusting to the middle school?

To complete the project, Ms. Bo had each student show their movie, one after another. She used the expectations as her assessment rubric, and graded them as the students showed the movies. Sitting in the classroom, listening to the students say, "Awwww!" and, "I love horses, too!" was amazing. All the students' personalities piled up on top of each other, and you could feel the group coming together as a class that cared about their classmates because each one was known.

I thought about including some samples of the videos, but then I thought about how personal each one was. Even though the students gave me permission to share their work, I didn't want to publish videos with that much personal information. That said, here's a photo of students watching the videos during class:

Wednesday, March 5, 2014

Reading the Forum

|

| The only picture of me speaking at the Forum because the students were speaking the rest of the time. |

And we made people cry.

Not the bad kind of crying, where people are sad. The good kind of crying, where people are so amazed by the insights of the youth that the experience is cathartic for the participants. Behar (1996) writes about this sort of ethnography in The Vulnerable Observer: Anthropology that Breaks Your Heart, saying, "I think what we are seeing are efforts to map an intermediate space we can't quite define yet, a borderland between passion and intellect, analysis and subjectivity, ethnography and autobiography, art and life" (p. 174). The students presented their ideas in a traditional way, but as students, they're not the ones whose voices are typically heard in educational research. That was my goal with this presentation - not just to share my interpretations of their experiences but instead to have them share.

The students were looking at their ways of understanding audience in relationship to blog posts that were responded to by adults from around the country - some who agreed with them, and some who didn't. Their take-aways for teachers were:

- Place-based learning is memorable. (This because none of the four will ever forget that Robert Hemings, Thomas Jefferson's slave, was absent from a museum exhibit, and that led to deep discussions about what it means to write the Declaration of Independence when a slave is bringing you your slippers)

- Big audiences are good for revision. (This because all four students felt that the responses from people from around the country led them to consider deeply what they'd written and what they meant, and if the audiences' responses indicated that those two matched)

- Teachers have to be very aware of what it means to put student work out to a wide audience. (This because, as one of the students said, "It's scary. Really scary." Also because, as another student said, "When you know your work is going to be read by a lot of people, there's a lot that you won't say. A lot of topics that you're not willing to go into."

I was so incredibly impressed by the students' presentation, by their intelligence, and by their generosity in sharing their time for the Forum.

References:

Behar, R. (1996). The vulnerable observer: Anthropology that breaks your heart. Boston, MA: Beacon.

Erickson, F. (1986). Qualitative methods in research on teaching. In M.C. Wittrock (Ed.), Handbook of research on teaching (3rd ed.). New York, NY: MacMillan.

Tuesday, February 25, 2014

Digital Literacies and 911

*This post is about something that was pretty scary, and the ending isn't necessarily happy. I'm not graphic about it, but I wanted to give people a heads up.

Last night, I was leaving a meeting, looking at the train schedules on my phone. One of my friends shouted, "Bethany! Call 911." I heard a gasp and looked up. A woman had fallen on the ground, and she was having a seizure.

I called 911. We were on a busy street, and it was hard to hear the operator. Was the victim conscious? No. Was the victim breathing? Yes. Was the victim garble-garble? What? Was the victim garble-garble? I can't hear you! Keep the victim garble-garble. Don't garble-garble. I CAN'T HEAR YOU!

The operator hung up.

I stared at my phone. The operator had hung up. Brain didn't compute. Hurt person on ground. Help person. Cover person. Comfort person. Where ambulance?

I looked up. There was a huge crowd of people, and every single one of them was calling 911.

The ambulance came a few moments later, and the paramedics took over.

How does this incident speak to digital literacies? There's an article I really like, Vasudevan (2010), that considers the affordances of portable technologies like MP3 players, handheld video game players, and cell phones in relationship to literacy. Vasudevan writes, ". . .the value of these technologies is underrepresented in studies focusing on the intersections of literacies and technologies in the lives of youth who . . . are perceived to be on the margins of educational discourses" (p. 67).

For me, in an emergency, instinct takes over. I called 911 because someone told me to, not because I was actively engaging in digital literacy. Looking at the way the group operated, though, I see connections between digital literacies and the emergency.

Apparently, in Philly, there's a belief that ambulances take a long time, and sometimes they don't come. I can't say if that's true or not. What I know is, the people in the group believed it, and I heard a lot of comments like: "They come when a lot of people call," "The call dropped? Call them back," and, "Do you have a phone? You call 911, too." What I saw from that group of people in relation to portable technologies was an accessing of a shared belief (that 911 calls are more effective when multiple), a feeling of agency (that their phone calls would affect the speed of the response), human contact (working together to execute a plan), and digital literacy (in the sense that responders were using technologies to communicate rather than in the sense that they were using technologies to communicate through symbols like writing . . . that's an entire paper, though, so I'm not going to go into it).

I know that there are both problems and affordances related to cell phones, but last night I was really glad that we all had phones.

I hope that the woman who had the seizure is okay.

(PS I have a feeling that multiple calls to 911 could clog up the system, and I'm sure that some people will question that the group acted together to make multiple calls. I want to emphasize that the woman was in critical condition, the first call to 911 resulted in a hang-up, and an ambulance - with lights on - drove past while we were trying to get help)

Reference:

Vasudevan, L. (2010). Education remix: New media, literacies, and the emerging digital geographies. Digital Culture & Education. 2:1, 62-82

Last night, I was leaving a meeting, looking at the train schedules on my phone. One of my friends shouted, "Bethany! Call 911." I heard a gasp and looked up. A woman had fallen on the ground, and she was having a seizure.

I called 911. We were on a busy street, and it was hard to hear the operator. Was the victim conscious? No. Was the victim breathing? Yes. Was the victim garble-garble? What? Was the victim garble-garble? I can't hear you! Keep the victim garble-garble. Don't garble-garble. I CAN'T HEAR YOU!

The operator hung up.

I stared at my phone. The operator had hung up. Brain didn't compute. Hurt person on ground. Help person. Cover person. Comfort person. Where ambulance?

I looked up. There was a huge crowd of people, and every single one of them was calling 911.

The ambulance came a few moments later, and the paramedics took over.

How does this incident speak to digital literacies? There's an article I really like, Vasudevan (2010), that considers the affordances of portable technologies like MP3 players, handheld video game players, and cell phones in relationship to literacy. Vasudevan writes, ". . .the value of these technologies is underrepresented in studies focusing on the intersections of literacies and technologies in the lives of youth who . . . are perceived to be on the margins of educational discourses" (p. 67).

For me, in an emergency, instinct takes over. I called 911 because someone told me to, not because I was actively engaging in digital literacy. Looking at the way the group operated, though, I see connections between digital literacies and the emergency.

Apparently, in Philly, there's a belief that ambulances take a long time, and sometimes they don't come. I can't say if that's true or not. What I know is, the people in the group believed it, and I heard a lot of comments like: "They come when a lot of people call," "The call dropped? Call them back," and, "Do you have a phone? You call 911, too." What I saw from that group of people in relation to portable technologies was an accessing of a shared belief (that 911 calls are more effective when multiple), a feeling of agency (that their phone calls would affect the speed of the response), human contact (working together to execute a plan), and digital literacy (in the sense that responders were using technologies to communicate rather than in the sense that they were using technologies to communicate through symbols like writing . . . that's an entire paper, though, so I'm not going to go into it).

I know that there are both problems and affordances related to cell phones, but last night I was really glad that we all had phones.

I hope that the woman who had the seizure is okay.

(PS I have a feeling that multiple calls to 911 could clog up the system, and I'm sure that some people will question that the group acted together to make multiple calls. I want to emphasize that the woman was in critical condition, the first call to 911 resulted in a hang-up, and an ambulance - with lights on - drove past while we were trying to get help)

Reference:

Vasudevan, L. (2010). Education remix: New media, literacies, and the emerging digital geographies. Digital Culture & Education. 2:1, 62-82

Thursday, February 13, 2014

Snow Day Science

When I first started teaching, I taught at a preschool founded on Reggio Emilia theories. My mentor had an amazing way of considering children's interests and merging them with science and art . . . I'm pretty sure that this came from her.

Today, my son, Arden, had a snow day. We spent the morning sledding, but in the afternoon, the snow had turned to rain. It was too rainy to go outside, and he still wanted to play in the snow. Taking my lead from Reggio Emilia theories, I considered his interests - touching snow, scooping, and measuring - and we did this experiment.

Arden measured and scooped the snow into bags:

I held the bags open while he put colors into them. In this one, he mixed blue and yellow.I asked, "What color do you think blue and yellow will make?"

He said, "Brown."

I said, "Let's see if your prediction is right."

We sealed up the bag, and he mashed up the snow. When he saw that the snow was green, he shouted, "Yellow and blue make green!"

I was pretty psyched.

We repeated the experiment with yellow and red and then red and blue. When we were done, we laid out all the bags in rainbow order.

After making all our colored bags of snow, we put the extra snow in the sink.

I asked, "What's going to happen to the snow?"

He said, "It water."

I asked, "So snow is water?"

"Yes," he said. "It cold."

I said, "That's called a phase change. Water can be liquid, solid, or vapor, like steam."

He said, "Phase change?"

I don't think he really got the idea of liquid, solid, or vapor, but he understood that snow was cold water, so I left it at that for today.

Arden especially enjoyed flinging the snow under the faucet.

The connection between Reggio Emilia theories - following student interests to develop a deep understanding of concepts - relates to digital media ideas like the Maker Movement, Connected Learning, and Participatory Cultures (Jenkins et al., 2006) in that playing and exploring are considered to be valuable parts of the learning process. This often makes learning incredibly messy (for example, explaining to Arden that the food coloring wasn't going to come off his hands right away didn't go so well, he was only interested in the project while he was measuring and smashing, and the only color he was truly interested in making was brown, even though I was convinced that making a full rainbow was VERY important), but when he shouted, "Blue and yellow make green!" and explained that snow was water, he was both messing around and learning key scientific ideas.

Also, it was a heck of a lot more fun than staring out the window and wishing we could go sledding some more.

References

Jenkins, H., Clinton, K., Purushotma, R., Robison, A. J., & Weigel, M. (2006). Confronting the challenge of participatory culture: Media education for the 21st Century. Retrieved from The John T. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation: http://digitallearning.macfound.org/atf/cf/%7B7E45C7E0-A3E0-4B89-AC9C-E807E1B0AE4E%7D/JENKINS_WHITE_PAPER.PDF.

Monday, February 10, 2014

Hidden History, Moonstone Arts, and Why I Love Writing in Groups

Saturday was the Charlotte Forten Writing Workshop (put on by the Philadelphia Writing Project, NMAJH, and Moonstone Arts).

Saturday was the Charlotte Forten Writing Workshop (put on by the Philadelphia Writing Project, NMAJH, and Moonstone Arts).When I was young, I thought that the reason there weren't any women in history books (other than in special block sections proclaiming that they were, in fact, important) was because women really hadn't done anything important.

That is not a lie. That was hegemony in practice*.

That might be why I love Moonstone Arts's Hidden History series. It's an opportunity to learn about people who don't make it into the history books or who only get a special block section.

The workshop on Saturday brought together students, teachers, parents, grandparents, actors, and scholars. Elijah Pringle, Jonathan Steadman, and Bethlehem presented Charlotte Forten's journal entries by having Jonathan act as interviewer and Bethlehem play the role of Charlotte Forten reading from her journal. At every 'commercial break,' Elijah gave students a writing prompt that related to the journal entry. At the end of each break, we shared what we wrote.

Charlotte Forten was an abolitionist, educator, member of Port Royal Experiment, Philadelphian, and writer. Her journals (where she casually mentions meeting Colonel Robert Shaw) provide a first-hand account of living before, during, and after the civil war.

Charlotte Forten was an abolitionist, educator, member of Port Royal Experiment, Philadelphian, and writer. Her journals (where she casually mentions meeting Colonel Robert Shaw) provide a first-hand account of living before, during, and after the civil war.This photo is of Bethlehem playing the role of Charlotte Forten as she read Forten's 6/2/1854 response to the decision against Anthony Burns:

And if resistance is offered to this outrage, these soldiers are to shoot down American citizens without mercy; and this by the express orders of a government which proudly boasts of being the freese in the world; this on the very soil where the Revolution of 1776 began; in sight of the battle-field, where thousands of brave men fought and died in opposing British Tyranny, which was nothing compared with the American oppression to-day. I can write no more. A cloud seems hanging over me, over all our persecuted race, which nothing can dispel.The writing prompt we used with this was, "What do you witness in the world around you? How do you feel about it? Write a journal entry about something you have seen that stirred your emotions."

Throughout the workshop, the writing ranged from poignant to silly, and each time someone shared her writing, I was reminded of why I love writing in groups: because everyone can be inspired by the same passage, and there's something amazing about the differences in people's responses.

At the end of the workshop, everyone got free admission to the museum. That was when I saw this book. I cannot tell you how happy I am that there's a book called My First Kafka. Sigh. Love post-modernism when it does things like this.

At the end of the workshop, everyone got free admission to the museum. That was when I saw this book. I cannot tell you how happy I am that there's a book called My First Kafka. Sigh. Love post-modernism when it does things like this.

Although this post is way, way too long, I'm going to put in links to two videos made by participants in the NMAJH Story Corps booth. You have to link through the captions because Blogger and Story Corps didn't want to format nicely together.

|

| Take Me Out to the Ballgame |

|

| What Does Freedom Mean to You? |

At the end of the day: found this on a table tent. Thank YOU, Emilie and Pam, for participating!

If you're interested in getting a copy of the booklet that we gave to participants (because it's awesome), email larrymoonstoneartscenter.org to find out more.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)